The Story Behind the Zeta Beta Tau Credo is as timely as ever

Published August 2020

Watch as Brother Greer discusses the writing of the Credo

Civil rights protests. Calls for change. Questioning the value of Fraternity.

These words may describe our world today. They also describe what was taking place in 1963 when the delegates at the 1963 Zeta Beta Tau Convention adopted the Credo of ZBT. The creation was a response to the anti-Fraternity movement that was taking place on college campuses. Sound familiar?

In the face of rising “Abolish Fraternities” movement, it is more important than ever to remember why the Credo was created and how it calls on ZBT’s to act. The following article was published in the 2013 version of the Deltan and is as relevant today as it was then.

THE CREDO OF ZETA BETA TAU

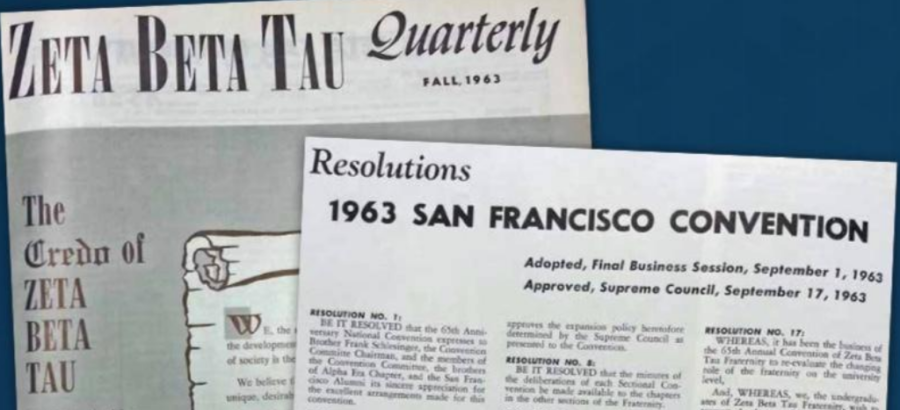

Resolution 17 of the 1963, San Francisco National Convention

By: James E. Greer, Jr., Beta Pi (California State University, Long Beach) ’64

Many believe the mid-20th Century’s seismic movement in American culture began in the late 1960s, but in fact strong winds of change were felt a decade earlier. In 1960 John Kennedy became president and his inaugural speech made clear the country was now in the hands of a new, restless generation impatient for change. As a Catholic, his very election was a signal that something big and heretofore unknown was going on in America.

The civil rights push, increased concern for the disadvantaged and impatience with continuing poverty, a new attitude regarding our relationship with the world and a questioning of old values and customs gave energy to many movements demanding something new. The Protestant Ethic and WASP domination of American culture was dead or dying. The free speech movement was running wield at Berkeley. Campus humor magazines all over the country were lampooning the status quo in every aspect of national and university life and often liking fraternities to dinosaurs whose demise would be a good riddance.

College students were spending summer vacations in the south registering voters or marching in street demonstrations on behalf of farm workers. Continued support of tradition, heritage and brand by many fraternity members and their insistence on being excused from communal responsibility and academic performance was increasingly seen as prejudice, elitism and shameful behavior. Fraternity’s cry for prerogatives and preferences clashed with the new demands for equality of opportunity, universal participation and insistence on doing something worthwhile for others as a condition of

continued institutional recognition and community approval.

So, it’s not surprising that in 1963 at the ZBT Convention, a group of students got together to discuss the situation and equally not surprising, at least for ZBT, that this student group attracted several supportive alumni national officers who encouraged their efforts. These were the same national leaders who made the great post war changes in ZBT – inclusive membership and wide – community commitment. The members of the group which became a convention committee, attended school in the Ivy League and the Big 10, at prestigious small liberal arts schools and secondary state universities.

They came from all corners of the country and from the heartland. They were Jewish and Christian, black and white. They were every ZBT.

They began their discussions concerned about fraternity’s continuing relevance in the face of a radically changing society. They recognized the irony of the country’s increased demand for social justice and its relationship to ZBT’s most treasured principle – that humankind is only right with itself when committed to Justice and Righteousness for all. They felt a great need to do something, say something that at least for ZBT would make it clear that fraternity, as originally conceived was forever relevant, indeed a vital force for good.

They knew the challenge was to enlarge ZBT’s vision beyond traditional self-congratulatory absorption. The trick, they thought, was to show that we could be committed to something beyond just ourselves while continuing the social bond of brotherhood.

When the students reached a consensus on what they wanted to say, Jack London, a brilliant New York City attorney and national president elect helped them find the right words. Their thesis was simple – the purpose of the University and Fraternity was to give society citizens who were intellectually adventurous and achieving, socially committed to making a better world, honest and fair and responsible for the protection and well-being of all.

In other words

• Intellectual Awareness

• Social Responsibility

• Integrity

• Brotherly love

The statement was fashioned into a resolution, presented to the chapter delegates and unanimously adopted. Those in attendance left the convention and San Francisco with a clear vision of what ZBTs must do. And during the dark days of the late sixties and early seventies, the Credo was often the one clear statement our undergraduates would point to with pride and say, this is what I believe and what I will do. Because of their example the Fraternity came to understand over the years that ZBT does not need more admirers of the Credo. There are lots of those. The Fraternity needs doers of the Credo. Each member must ask himself if he will be a doer of the Credo. The brothers of that summer convention, fifty years ago would hope the Credo continues as a statement of ZBTs faith in itself and as a navigational system for purpose driven action.